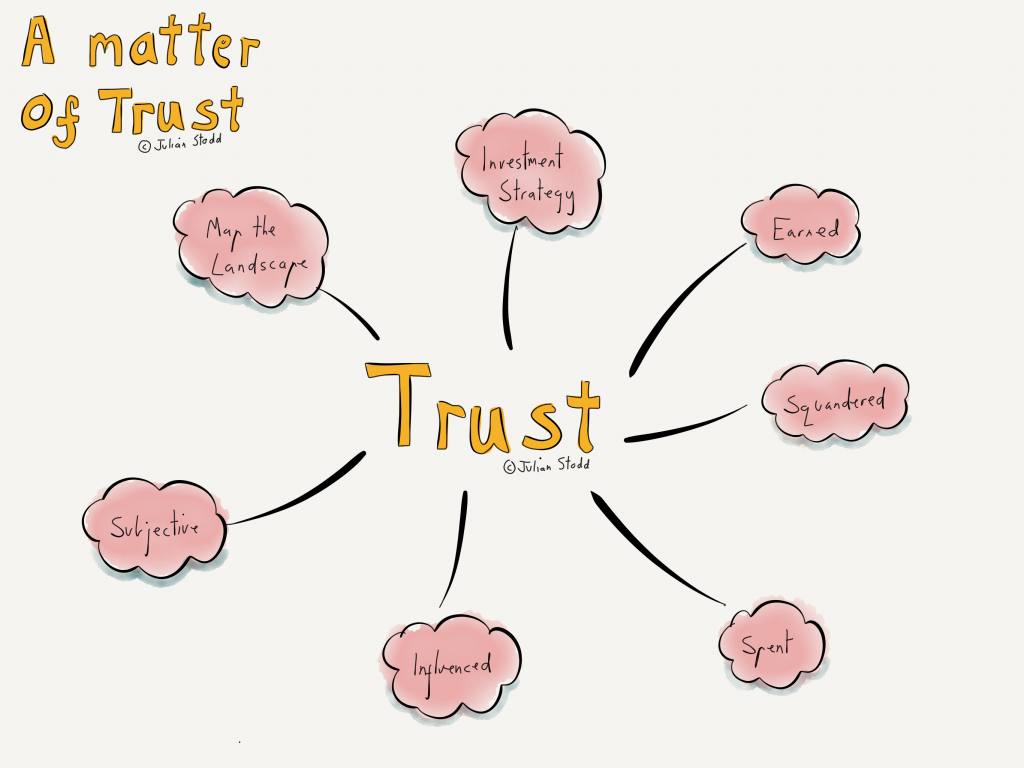

Trust is complicated: a subjective term that, when we try to analyse it and share consensus, reveals more nested sub- concepts each as ephemeral as the one that came before it. And yet we know it: we know trust, we feel it, we build it, and squander it. Trust can be invested or misplaced, it can be carefully considered or blindly given. We know types of trust: the trust that exists between parents and children, between siblings, between friends, these types of trust are typically unwritten, deeply bonded, but unquantifiable. Other types of trust exist: we can view contracts and legal bonds as types of codified trust, attempts to remove ambiguity and introduce formalised consequence, but somehow these things feel different.

When it comes to the nature of trust between an individual and the Organisation that they work for, instinctively it feels as though we are looking at a multilayered relationship. Certainly, there is a contractual element which defines behaviours and remuneration, formal expectations, and processes of consequence when these expectations are not met (or this trust is breached). But that is not the limit, that alone is not what it means to have

When it comes to the nature of trust between an individual and the Organisation that they work for, instinctively it feels as though we are looking at a multilayered relationship. Certainly, there is a contractual element which defines behaviours and remuneration, formal expectations, and processes of consequence when these expectations are not met (or this trust is breached). But that is not the limit, that alone is not what it means to have trust at work.

We also invest a different type of trust in organisations, treating them in some ways as though they are individuals. The type of trust that we see between individual and organisation is interesting in that it can hold multiple concurrent views of reality. I may trust the people that I work with, the people in this office, but be suspicious of our counterparts in the office on another continent. I may trust my manager, except when it comes to annual performance reviews, when I realise that they are just a mouthpiece for an organisation that doesn’t want to give me a pay rise. I may believe in what the business does, and yet have no trust that they will look after me along the journey. The ways that trust is experienced between individual and organisation forms a complex landscape and is the subject of my most recent research.

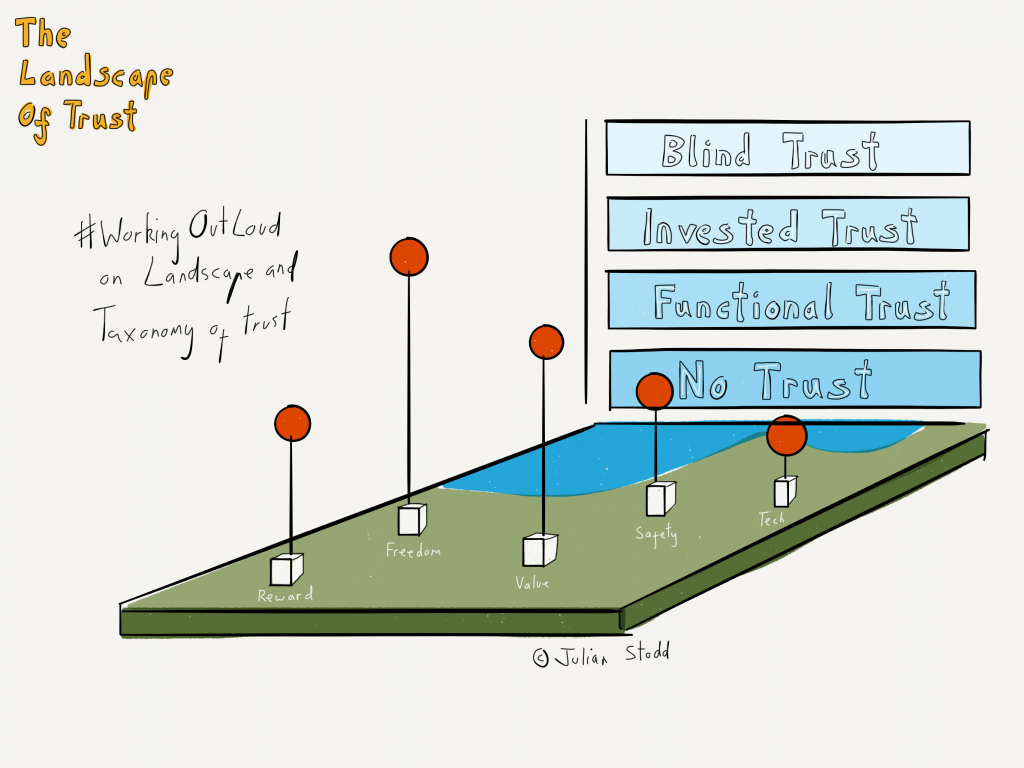

There are functional types of trust: background layers, such as a belief that you will be paid at the end of the month, which allow us to operate, but do little to novate or engage, and there are invested types of trust, the types that draw us in, which hold power over us.

I’m interested in the Landscape of Trust, this subjective network of nested notions that we feel so strongly, and yet often lose, sometimes without even realising it. My work covers the Social Age: the new reality we find ourselves in, a new nature of work, a new nature of knowledge, a new Social Contract between individual and organisation. In the Social Age some organisations resist change, many are constrained within it, thrashing and churning and trying to change the formal aspects of the organisation, the teams and structures, processes and systems, desperately trying to capture an agility that often eludes them.

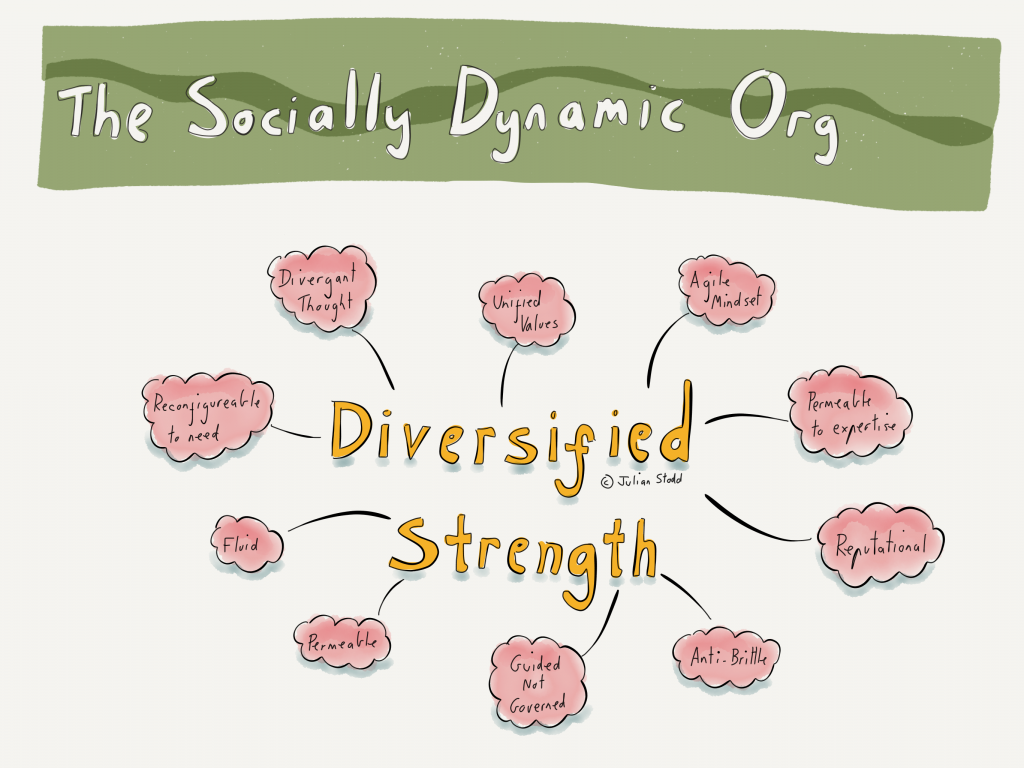

If we understand it, we can create the Socially Dynamic Organisation, an organisation that understands both how formal systems work, the ones that are under the control of the organisation, and social systems, social ways of working, learning, and leading, where the strength comes from invested and engaged communities. You cannot demand the Socially Dynamic organisation because it is founded upon trust: so to create it, together, we have to earn that trust. The way that the strength of the Socially Dynamic Organisation is invested in people give it a diversified strength: strength not simply through infrastructure and process, but through reputation and trust.

The Landscape of Trust is just that: an attempt to capture what ‘trust’ means to different people, to tease out common elements, to understand where, if anywhere, elements are opposed or can be opposing. For example, in the early research we have seen that to feel ‘valued’ people wish to be ‘rewarded’, whilst to feel ‘trusted’ they must have ‘freedom’. So feeling ‘valued’, and feeling ‘trusted’, may be different things, or at least may provide an interesting part of the Landscape for us to explore. Even more interesting, only around 40% of people wish for financial reward: most wished for opportunities and the chance to build a legacy.

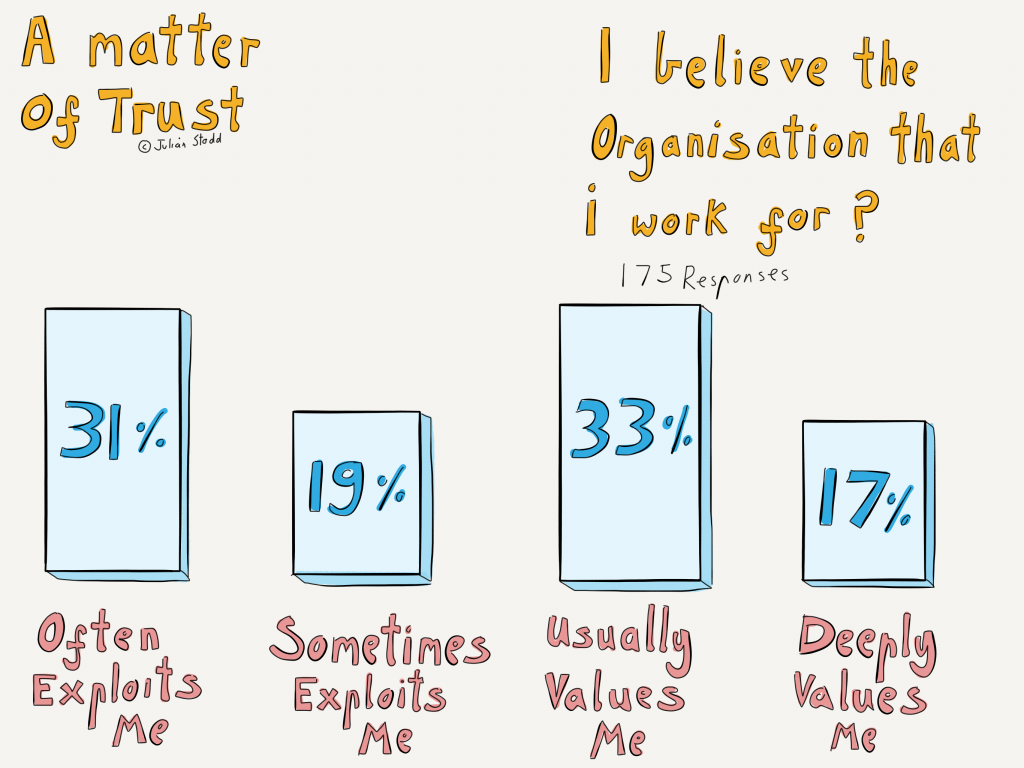

This is early-stage research, already there are some interesting, if potentially worrying, results: 54% of people said that they have low or no trust in the organisation that they work for. 50% of people feel ‘somewhat’ or ‘highly’ valued, whilst the other 50% feel that the organisation ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ exploits them.

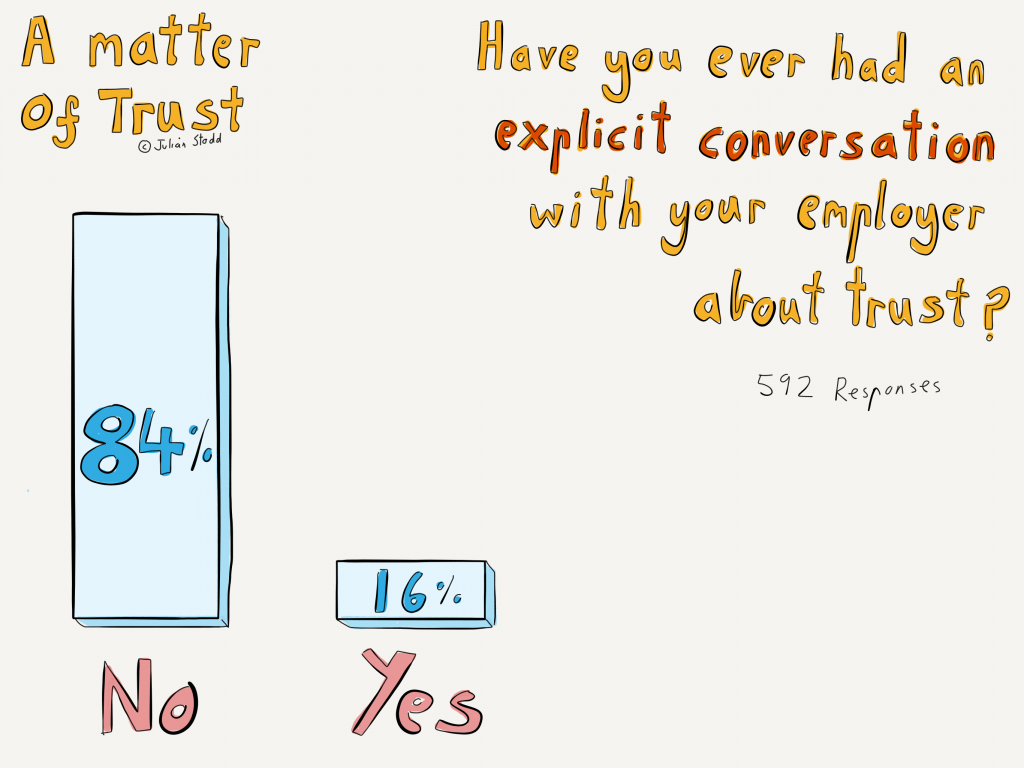

Less than 20% of people invest their trust ‘blindly’, but less than 20% have had an explicit conversation about trust at work. And if trust is missing, just over 30% say that they are more likely to leave the organisation, whilst the rest say that they are less likely to ‘engage’, to ‘help’ others, or to ‘share’, all of which are key behaviours for the Socially Dynamic Organisation.

The ultimate aim of this work is to baseline what the Landscape of Trust looks like across different organisations, different cultures and sectors, and to use this to target specific interventions to build trust. This will be a project of marginal gains: to have a competitive advantage, we don’t need to double our effectiveness, we simply need to earn progressively more trust, and to squander progressively less: we maybe need a more level landscape, not the pits and troughs of the organisation that cannot maintain ‘trust’ at an invested level.

Part of this work involves looking at the Taxonomy of Trust, across four levels, which run from having ‘no trust’, through to the second level of ‘functional’ trust, the bare minimum we need to run an organisation, then on to ‘invested’ trust, that which we as leaders and future leaders, as Social Leaders of the organisation must seek to build, and finally through to ‘blind’ trust, which may not be a good thing, which can contribute to failed or fractured cultures where there is little permission or incentive to question.

The aim is not to score an organisation or individual on trust, but rather to understand the ways that it is manifest and experienced within any specific organisation, and to understand the ways that we can influence and earn this most valuable of commodities. There are things that we, as leaders and community members, can do to make the organisation more fair, more equal, more worthy of invested trust.